Biblical origins

- First of all, the Bible, including the Old Testament, the idea of a jubilee comes from the Book of Leviticus (25:8-13). This book is the third of the five books of the Torah. It owes its name to the term “Levite”, referring to members of the tribe of Levi, traditionally in charge of the Temple and from which the priests are descended. It speaks of priestly duties in Israel. It states:

08 You will count seven weeks of years, that is, seven times seven years, or forty-nine years. 09 In the seventh month, on the tenth of the month, on the Feast of Atonement, you shall blow the horn for the ovation; on that day, in all your land, you shall blow the horn. 10 You will make the fiftieth year a holy year, and you will proclaim liberation for all the inhabitants of the land. It will be a jubilee for you: each of you will return to his property, each of you will return to his clan. . 11 This fiftieth year shall be a year of jubilee for you: you shall not sow the seed, you shall not reap the grain that has grown by itself, you shall not harvest the untrimmed vine. 12 The jubilee shall be holy to you; you shall eat what grows in the field. 13 In this jubilee year, each of you will return to his own property.

So every fifty years, the Israelites celebrated a Jubilee. It was a year of liberation and rejoicing, when slaves were freed, debts cancelled, and land returned to its original owners. This year was seen as sacred, a time for the land to rest and for people to devote themselves to God and family.

- Then, in the New Testamentthe idea of forgiveness and spiritual renewal, particularly in Jesus’ teaching on mercy and forgiveness, also influenced the notion of jubilee in Christianity.

Its history

- In 1300 , Pope Boniface VIII established the first Holy Year. And it was the pilgrims themselves, many of whom were in Rome that year, who asked him to do so. The climate was propitious. Under the influence of Franciscan spiritualists and their master thinker, Joachim de Flore (12th century), Western Christendom was experiencing a period of eschatological and apocalyptic tension. The papal bull of February 22, 1300 granted complete remission of sins and the lifting of penalties to all those who, after confession, visited the Roman basilicas of St. Peter and St. Paul every day for two weeks. To ensure that no generation was deprived of the benefits of this exceptional indulgence, Boniface VIII fixed the interval between two Jubilees at fifty years. This decision introduced into the Western Latin Church the custom of the jubilee, a one-year period marked by an overabundance of divine mercy and qualified, for this reason, as a “holy year”.

- From the mid-15th century onwards, jubilees were held every twenty-five years. The conditions for obtaining the jubilee indulgence had already been extended by the addition of the Lateran and Santa Maria Maggiore basilicas to the previous two. The rite of opening and closing the holy doors of the four major basilicas dates back to the pontificate of Alexander VI Borgia (1499).

- The spiritual dimension of the Holy Year was further enhanced by the Catholic Reformation in 1575. The Jubilee pilgrimage became a vast undertaking of collective penitence and mortification around the Roman Pontiff. Pilgrims needed courage! The dangers of the journey were compounded by difficulties on the spot: finding accommodation, food, getting around in the city, avoiding pickpocketing… After the great Protestant split, hospitality and accommodation expanded to match the scale of the pilgrimage, which continued to draw crowds to Rome from European nations that had remained faithful to the Roman Catholic Church.

- The slow de-Christianization of the 18th century, the revolutions of the 19th, and the decline and collapse of the popes’ temporal power brought the jubilee to a halt for a century (1825-1925). The Holy Years of 1850, 1875 and 1900 were proclaimed but not celebrated. Six jubilees, including two extraordinary ones, punctuated the 20th century: 1925 and 1933 (1900th anniversary of the Passion of Christ, Pius XI), 1950 (Pius XII), 1975 (Paul VI), 1983 (Jubilee of the Redemption) and 2000 (John Paul II).

- Since 1300, popes have progressively extended the scope of the Jubilee. In 1950, Pius XII proclaimed the universal nature of the Jubilee indulgence. From then on, it was no longer necessary to travel to Rome. The Holy Year is now seen as a high point in the life of the Church – a time of conversion, penance, forgiveness and thanksgiving – and as the fruit of a pontifical policy aimed at rallying the faithful around the person of the Pope.

- History now records twenty-nine holy years, including 2025.

Ref / Monique Maillard-Luypaert, diocese of Tournai, 2025

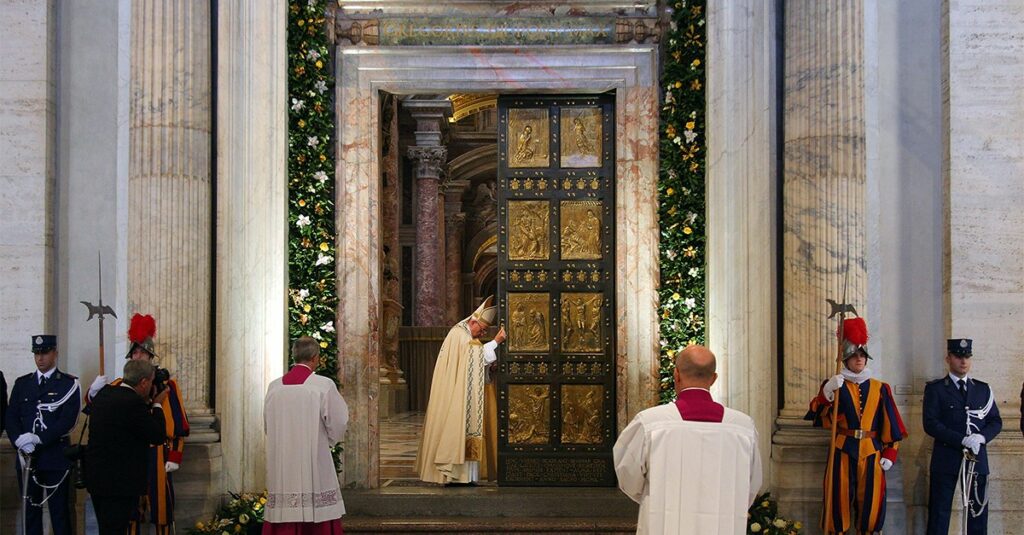

The Holy Door

- The Holy Door is a reminder of the responsibility of every believer to cross its threshold: it’ s a decision that presupposes the freedom to choose, and at the same time the courage to give up something, to leave something behind (cf. Mt 13:44-46); passing through this door means professing that Jesus Christ is Lord, strengthening our faith in him, to live the new life he has given us. This is what Pope John Paul II announced to the world on the very day of his election: “Open wide the doors to Christ.”

- A Holy Door is the concrete translation into our daily lives of the image that Jesus himself applies to himself in the Gospel: “I am the door. If anyone enters through me, he will be saved. (John 10:9).

- The Holy Door of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome was first opened at Christmas in 1499. On December 24, 2024, Pope Francis opened it again to mark the start of the Holy Year Jubilee “Pilgrims of Hope”.

- A Holy Door is present in Rome’s four major basilicas: Saint John Lateran (the pope’s cathedral), Saint Peter’s, Saint Mary Major and Saint Paul Outside the Walls.